- Empty cart.

- Continue Shopping

The Liberal Monument: Urban Design and the Late Modern Project

₹1,800.00

- By Alexander D’ Hooghe

- Hardcover: 240 pages

- Publisher: Princeton Architectural Press (1 December 2010)

- Language: English

- ISBN-10: 1568988249

- ISBN-13: 978-1568988245

- Product Dimensions: 16.5 x 1.9 x 23.5 cm

2 in stock

Architect Alexander D’Hooghe believes urban design has lost its way. Once among the most articulate and avant-garde of disciplines, the field now lacks, he suggests, the confidence necessary to address its most critical challengesprawl. In his provocative manifesto The Liberal Monument, D’Hooghe argues that architecture and urbanism must boldly intervene in city planning and growth management. This strategic use of architecture represents, for him, the last hope to revitalize the “quasi-endless gray carpet” spreading between theworld’s urban centers. D’Hooghe’s starting point requires a reassessment of discarded, sometimes disgraced, late-modern theories of placemaking. D’Hooghe points out that the very idea of top-down urban planning and monumentalized space was jettisoned due to its commonly held associations with the monumental neoclassicism andsymbolism employed by Nazi architect and urban planner Albert Speer. D’Hooghe respectfully posits that we should not allow this perversion of thought to preclude our own thinking at the scale of urban planning.

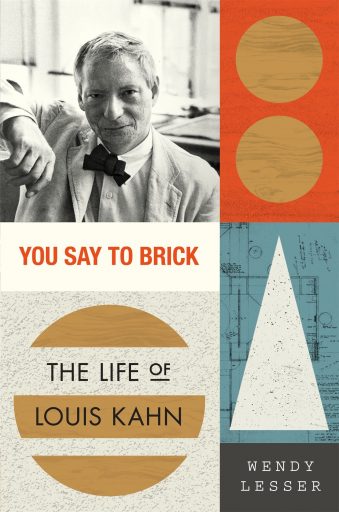

D’Hooghe travels the world in search of experiments in urbanism and findsin the ruins of these failed utopiasa way forward. He discovers in the work of “second-generation” modernists Sigfried Giedion and Louis I. Kahn an effort to connect architecture, planning, and liberal politics. This becomes the seed for what he calls “the liberal monument.” The Liberal Monument is a provocative, accessible work of theory that challenges all of the accepted truths of urban design. Its goal is to restore the confidence architecture will need, whether it is building cities from the ground up in China and Dubai or managing the growth of the sprawling suburbs of Phoenix and Raleigh/Durham.